- Introduction

- What Is Sumo?

- A Thousand Years of Sumo History

- Rituals and Symbolism — The Sacred within the Sport

- Life Inside a Sumo Stable

- Rankings and Divisions

- The Six Annual Tournaments (Honbasho)

- Watching Sumo — A Practical Visitor’s Guide

- The Modern Face of Sumo

- Why Sumo Matters

- Experiencing Sumo in Tokyo — A Model Day

- Philosophy within the Ring

- Conclusion

Introduction

Sumo is more than Japan’s national sport.

In a clay ring barely four and a half meters across, two wrestlers collide with the weight of centuries behind them.

Every stomp, every clap, every bow echoes an ancient rhythm — a ritual of power, purification, and respect.

It is a living link between religion, discipline, and performance; a mirror reflecting the Japanese sense of harmony between body and spirit.

This guide unpacks that world — its origins, its rituals, its wrestlers, and the practicalities of seeing it in person.

What Is Sumo?

Sumo is Japan’s traditional form of wrestling, combining athletic combat with Shinto ritual.

Two competitors (rikishi) face off in a circular ring (dohyō). The first to step outside or touch the ground with any part of the body other than the soles of the feet loses.

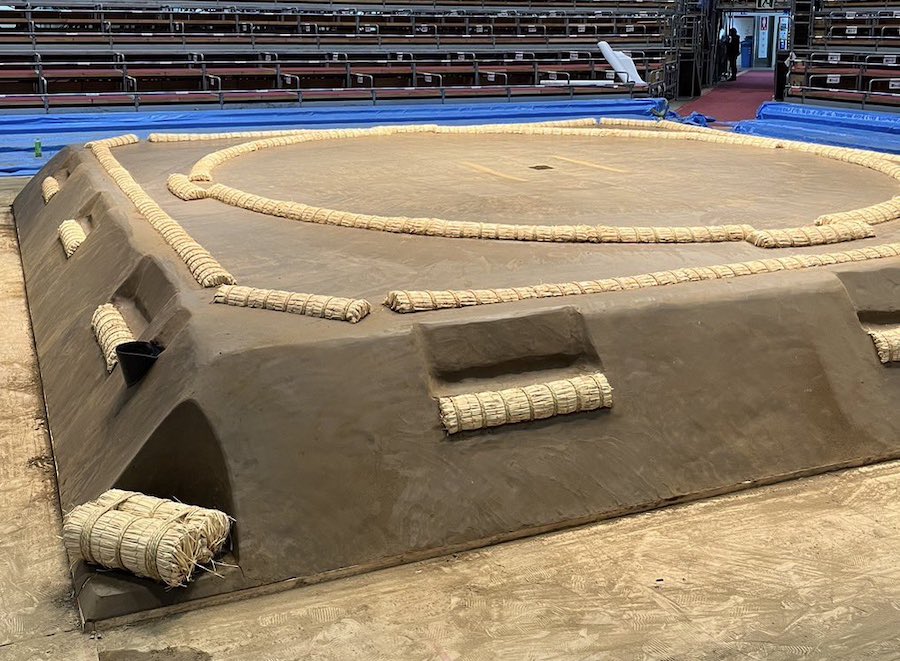

Yet beneath these simple rules lies a deeply spiritual philosophy. The dohyō is a sacred space; salt purifies it, stomping drives away evil, and the referee (gyōji) dresses not like a sports official but like a priest of an earlier era.

Core Elements

- Dohyō: A raised clay ring about 4.55 m wide and 34–60 cm high, edged with rice-straw bales.

- Mawashi: The thick belt or loincloth worn by wrestlers — cotton for training, silk for ceremony.

- Gyōji: The referee, wearing colorful Heian-era robes and carrying a fan (gunbai) symbolizing judgment.

- Shiko: The powerful leg-stomping exercise to test balance and symbolically crush evil spirits.

- Salt-Throwing: A Shinto purification ritual before each bout.

A typical match lasts only a few seconds, yet every gesture — bowing, crouching, clapping — is centuries deep in meaning.

A Thousand Years of Sumo History

Mythic Beginnings

Sumo’s roots appear in Japan’s oldest chronicles, Kojiki (712 AD) and Nihon Shoki (720 AD), describing a contest of strength between the gods Takemikazuchi and Takeminakata.

Early sumo was a Shinto ritual to entertain the kami and ensure bountiful harvests.

Feudal and Samurai Eras

By the 12th century, sumo served as combat training for samurai — a test of strength, agility, and courage.

During the Kamakura and Muromachi periods, it also appeared as a court performance, valued for both discipline and spectacle.

Edo Period: The Birth of Professional Sumo

From the 17th century onward, sumo became public entertainment.

Tournaments were organized to raise funds for temples and shrines, evolving into ticketed spectacles in Edo, Osaka, and Kyoto.

Many features of modern sumo — the ranking system, stable (heya) structure, referee dress, and dohyō design — were formalized in this era.

Modernization and National Symbol

After the Meiji Restoration (1868), Japan sought to preserve traditional arts while embracing modernization.

Sumo became a national emblem, blending ancient ceremony with a professional sports framework.

The Japan Sumo Association was established, standardizing tournaments and rankings.

Post-World War II television broadcasts brought sumo into living rooms across the nation, transforming it into a shared cultural experience.

Rituals and Symbolism — The Sacred within the Sport

Sumo’s appeal lies as much in its ritual as in its combat. Every match is framed by ceremonies drawn from Shinto practice.

The Dohyō-Matsuri (Ring Festival)

Before each tournament, a new clay ring is built and consecrated. Offerings of salt, sake, rice, kelp, and nuts are buried in the center to purify the ground and invite the favor of the gods.

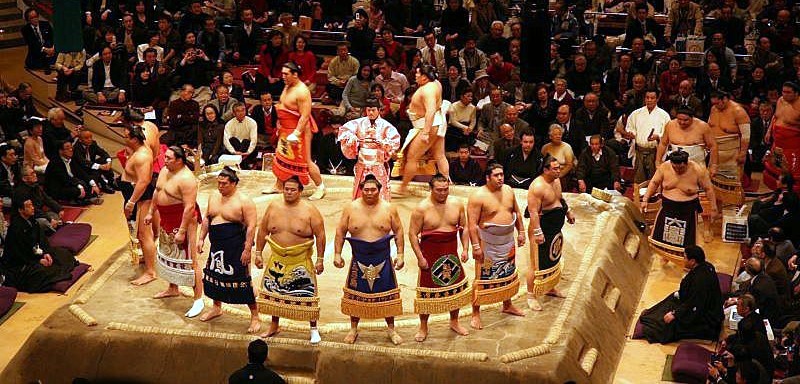

The Yokozuna’s Ring-Entering Ceremony

The grand champion (yokozuna) performs a solemn ritual before the crowd: raising his arms to the heavens, stamping the earth, driving out evil.

Accompanied by attendants — the tachimochi (sword bearer) and tsuyuharai (dew sweeper) — the yokozuna embodies dignity and divine strength.

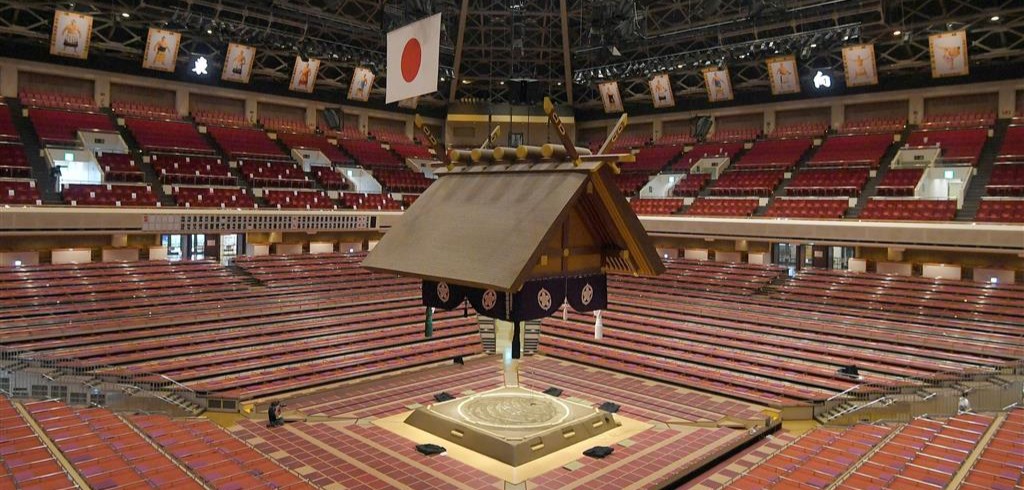

The Suspended Roof (Tsuriyane)

Above the ring hangs a roof resembling a Shinto shrine, complete with tassels in four colors representing the cardinal directions and seasons.

The ring thus becomes a miniature shrine — a sacred stage within the arena.

Salt, Stomps, and Silence

Salt purification (shio-maki), rhythmic stomping (shiko), the deep bows before and after a match — all symbolize respect: to the opponent, to the spectators, and to unseen forces.

For spectators, understanding these gestures transforms sumo from a clash of giants into a dance of faith.

Life Inside a Sumo Stable

A sumo stable (heya) is both home and school.

Young recruits, often teenagers, live together under the supervision of an oyakata (stable master, usually a retired wrestler).

Their daily life follows strict hierarchy:

- Morning Training: Begins before dawn; dozens of practice bouts, repetitions of shiko, and pushing drills.

- Meals: The famed chanko nabe, a protein-rich hot pot eaten communally.

- Household Duties: Lower-ranked wrestlers cook, clean, and serve seniors.

- Discipline: No alcohol before practice, no late nights, meticulous etiquette.

Becoming a professional wrestler means devoting one’s life entirely to the sport — physically, mentally, and socially.

For many, sumo is not merely a career but a form of ascetic practice.

Rankings and Divisions

Professional sumo consists of six divisions, each reflecting a wrestler’s performance.

| Division | Japanese | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Jonokuchi | 序ノ口 | Entry-level, new wrestlers |

| Jonidan | 序二段 | Developing stage |

| Sandanme | 三段目 | Intermediate level |

| Makushita | 幕下 | Near-professional tier |

| Jūryō | 十両 | First salaried division (sekitori) |

| Makuuchi | 幕内 | Top division |

Within the Makuuchi division are the titled ranks:

- Komusubi (小結)

- Sekiwake (関脇)

- Ōzeki (大関) — champion class

- Yokozuna (横綱) — grand champion

Promotion and demotion depend on results from six official tournaments each year.

A yokozuna cannot be demoted; when his dignity or performance fades, he retires voluntarily — a gesture of honor rather than defeat.

The Six Annual Tournaments (Honbasho)

Sumo’s rhythm follows a six-tournament calendar, each lasting 15 days.

| Month | City | Venue |

|---|---|---|

| January | Tokyo | Ryōgoku Kokugikan |

| March | Osaka | Edion Arena Osaka |

| May | Tokyo | Ryōgoku Kokugikan |

| July | Nagoya | Dolphins Arena (Aichi Prefectural Gymnasium) |

| September | Tokyo | Ryōgoku Kokugikan |

| November | Fukuoka | Fukuoka Kokusai Center |

Each day progresses from lower divisions in the morning to elite bouts in late afternoon, climaxing with the yokozuna’s appearance.

The final day (senshūraku) often draws national television audiences of millions.

Watching Sumo — A Practical Visitor’s Guide

For travelers, attending a sumo tournament is one of Japan’s most memorable experiences.

Here’s how to do it right.

1. Buying Tickets

Official Source

Purchase through the Japan Sumo Association’s official site or its English partner, Ticket Oosumo.

Each tournament’s advance sale date is announced online. Popular days — the opening day, middle Sunday, and final — sell out within hours.

Price Guide

- Tamari-seki (ringside cushions): Closest to the ring; thrilling but risky — flying wrestlers land here! Photography and food are prohibited.

- Box Seats (Masu-seki): Tatami-style boxes for four; ¥38,000–¥48,000 depending on location.

- Arena Seats (Chairs): Comfortable, numbered seating on upper levels; ¥5,000–¥12,000.

Booking Tips

- Mark the presale opening date on your calendar — usually about one month before each tournament.

- Travel agencies sometimes bundle hotel and ticket packages.

- A limited number of same-day tickets are sold each morning at the venue, but lines form early.

2. Access to Major Venues

Tokyo – Ryōgoku Kokugikan

Located steps from JR Ryōgoku Station (Sōbu Line).

Inside, you’ll find the Sumo Museum, displaying historic photos, ceremonial aprons, and ranking charts.

When no tournament is held, entry is free.

Osaka – Edion Arena Osaka

Five minutes on foot from Namba Station, surrounded by shops and restaurants — perfect for combining with sightseeing.

Nagoya – Dolphins Arena

Inside Nagoya Castle Park, host of the July tournament.

Temperatures can soar, so bring water and a fan. The summer atmosphere is famously lively.

Fukuoka – Fukuoka Kokusai Center

About a 15-minute walk from Hakata Station.

During the November tournament, food stalls and winter illuminations create a festival mood.

3. Etiquette in the Arena

- Stay seated during bouts; move between matches only.

- Silence during rituals such as the yokozuna’s ring entrance.

- Never step onto the ring — it is sacred ground.

- No flash photography.

- Applaud politely rather than shouting continuously.

Morning bouts feature lower divisions; crowds build toward afternoon when the top stars appear.

From around 4 p.m., tension rises — the atmosphere during the final matches is electric.

4. Morning Practice Visits

Many stables open early-morning training (asa-geiko) to visitors by reservation.

Silence and respectful behavior are essential — no flash, no sudden movement, modest dress.

Watching wrestlers train at close range offers a rare glimpse of the sport’s discipline and spirituality.

5. Beyond Japan: Sumo Abroad

Occasionally, special overseas exhibitions are held — such as the 2025 Sumo London Tournament at the Royal Albert Hall, which sold out within days.

Such events show how this ancient Japanese art now fascinates global audiences.

The Modern Face of Sumo

Today’s sumo balances reverence for tradition with pressures of modernization.

International Influence

Foreign wrestlers from Mongolia, Eastern Europe, and the Pacific Islands have reached the sport’s highest ranks, proving that sumo’s spirit transcends nationality.

Cultural integration, however, demands adaptation — learning Japanese, following etiquette, and living under strict hierarchy.

Controversies and Challenges

- Debates continue over the exclusion of women from the dohyō, rooted in Shinto concepts of ritual purity.

- Health and lifestyle concerns among wrestlers — obesity, injuries, early retirement — spur reforms.

- Scandals over hazing and match-fixing have occasionally shaken public trust.

Yet through transparency efforts, international outreach, and cultural education, sumo remains resilient — both ancient and alive.

Why Sumo Matters

Sumo is not only Japan’s national sport; it is a reflection of its ethos.

- Respect: Wrestlers bow before and after each bout — honoring the opponent.

- Discipline: Years of training and obedience to hierarchy define strength.

- Purity: Rituals cleanse both space and spirit.

- Harmony: Even in fierce competition, the ideal is balance — wa.

Watching sumo is to see Japan compressed into motion — where ceremony meets sweat, faith meets force.

Experiencing Sumo in Tokyo — A Model Day

Morning: Attend a morning practice session (asa-geiko) at a Ryōgoku stable.

Afternoon: Visit the Sumo Museum, explore nearby Edo-Tokyo Museum or traditional restaurants.

Evening: Watch a tournament match at the Kokugikan. Feel the crowd hush as salt flies and drums roll.

Finish the day at a chanko nabe restaurant, sharing the same hearty stew that fuels the wrestlers — nourishment for both body and soul.

Philosophy within the Ring

Sumo, at its core, dramatizes universal truths:

the balance of humility and pride, effort and fate, strength and surrender.

Victory comes not from aggression alone but from inner composure — a distinctly Japanese notion of power through stillness.

The dohyō becomes a microcosm of life: we rise, we fall, we bow, and we begin again.

Conclusion

Sumo endures because it is more than sport.

It is ritual theatre, moral discipline, and cultural memory entwined.

When you watch two rikishi crouch, clap, and charge, you witness a dialogue between ancient gods and modern humanity.

Attend once, and you will understand why Japan calls sumo its kokugi — the national sport.

It is the heartbeat of a nation made visible in dust, sweat, and silence.

The Japanese version of this article is here.↓↓↓