- A Soft Light Through Paper

- Origins — When Paper Came to the Islands

- Paper Becomes Culture — From the Court to the Commoner

- How Washi Is Born — A Symphony of Water and Hands

- The Many Lives of Washi

- The Science Inside Tradition

- The Modern Journey — Decline and Revival

- Washi in the Contemporary World

- The Human Element — Touch, Sound, Silence

- Why It Matters — The Philosophy of Enough

- Epilogue — A Thousand Years in One Sheet

A Soft Light Through Paper

Hold a sheet of washi to the window.

Light seeps through its fibers like morning mist, and suddenly the paper seems alive.

It breathes.

It glows.

It carries warmth from the hands that made it.

Washi — traditional Japanese paper — is far more than a writing material.

It embodies how the Japanese have lived with nature: never fighting it, but learning to flow with it.

It is a material that connects mountain plants to human hands, water to sunlight, past to present.

For over a thousand years, washi has been used for calligraphy, painting, lanterns, folding screens, and sacred rituals.

It lined the walls of homes, filtered light through shōji screens, and preserved centuries of documents.

Even today, this ancient craft continues to evolve — finding new life in art, design, and even technology.

To understand washi is to glimpse how Japan sees beauty itself.

Origins — When Paper Came to the Islands

The story begins not in Japan, but in ancient China, where paper was first invented around two thousand years ago.

From there, papermaking spread across the Asian continent.

In the early eighth century, along with Buddhism and new systems of government, the technique arrived in Japan.

At first, paper was rare and sacred.

It was used to copy Buddhist sutras or record imperial decrees — a precious medium for spiritual and political words.

The earliest surviving Japanese papers, stored in Nara’s Shōsō-in treasure house, still retain their smooth texture after more than twelve centuries.

The secret of their survival lies in both nature and care: Japan’s humid climate, abundant clean water, and native plants made ideal conditions for papermaking.

Unlike the wood-pulp paper common in the modern world, washi is made from the inner bark of three shrubs: kōzo (paper mulberry), mitsumata, and gampi.

Their long, flexible fibers produce paper that is thin yet astonishingly strong.

And because these plants regrow after harvesting, the material is endlessly renewable.

Even in its earliest form, washi was already a conversation between humans and the living landscape.

Paper Becomes Culture — From the Court to the Commoner

By the Heian period (794–1185), papermaking had matured into a refined art.

Aristocrats of the imperial court wrote love poems and letters on papers tinted with soft colors — pale pink for spring, indigo for summer nights, gold-flecked cream for autumn.

They believed that the beauty of the paper itself could express the writer’s heart.

A well-chosen sheet of washi was as meaningful as the poem it carried.

As centuries passed, the craft spread beyond the palaces and monasteries.

In mountain valleys where pure streams ran year-round, villagers began producing paper for trade.

Each region developed its own character:

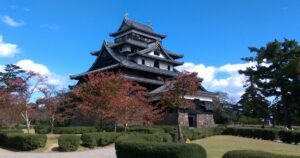

- Mino paper from Gifu — light and translucent, used for shōji screens.

- Sekishu paper from Shimane — thick and durable, perfect for documents.

- Hosokawa paper from Saitama — smooth, long-fibered, favored by calligraphers.

By the Edo period (1603–1868), Japan had become one of the most literate societies in the world.

Every school, shop, and household needed paper: for books, ledgers, umbrellas, lanterns, packaging, and ukiyo-e woodblock prints.

The rhythmic swaying of papermakers became part of the winter soundscape of the countryside — a steady heartbeat of daily life.

In that era, washi was not a luxury.

It was the skin of everyday Japan.

How Washi Is Born — A Symphony of Water and Hands

Papermaking in Japan still follows a rhythm set by nature.

The best time to work is winter, when cold water is cleanest and bacterial growth slows.

Snow may fall outside, but inside the workshop, clear water glistens in the wooden vats.

Preparing the fibers

Branches of kōzo are cut, steamed, and stripped of bark.

The white inner layer is boiled and beaten to separate fibers, then carefully cleaned by hand — every speck of dust removed with patient eyes and fingertips.

Forming the sheet

The fibers are suspended in water, mixed with neri — a viscous sap from the tororo-aoi plant.

This natural additive slows the water’s flow, allowing the fibers to float evenly.

Using a bamboo screen called su, the papermaker scoops, shakes, and rocks the mixture in a rhythmic motion known as nagashi-zuki — “flowing-scoop.”

The gestures look like dance, guided more by feel than by rule.

Layer after layer builds up until a thin mat of interwoven fibers appears.

Drying in the sun

The wet sheets are pressed, peeled, and brushed onto wooden boards.

There they dry slowly in the crisp winter air, becoming light yet strong.

The resulting paper carries traces of every element involved — water, wind, sunlight, and human touch.

Watch a craftsman at work and you will realize: washi is less a product than a performance between nature and hands.

The Many Lives of Washi

For more than a millennium, washi has taken countless forms — each revealing another aspect of Japanese life and thought.

A Medium for Calligraphy and Painting

Ink behaves differently on washi than on Western paper.

It sinks in softly, creating shades between black and gray, like breath turning visible.

Japanese calligraphers and painters have long relied on this responsiveness to capture subtle emotion.

The brushstroke doesn’t merely sit on the surface; it lives within the paper.

A Partner in Architecture

In traditional homes, shōji screens made of thin washi filter sunlight into a calm, diffuse glow.

The light becomes soft enough to live inside — neither glaring nor dark.

Architectural theorist Jun’ichirō Tanizaki called this interplay “the beauty of shadows.”

The paper doesn’t block light; it tames it.

A Material of Faith and Ceremony

At Shintō shrines, white zigzag paper strips flutter from ropes as symbols of purity.

Folded paper amulets and envelopes mark occasions of gratitude or mourning.

Even without words, washi conveys sincerity.

To fold paper is to show respect — an idea that links the art of origami to spiritual ritual.

A Guardian of Memory

Because it is acid-free and durable, washi is also used for conservation.

Museums in Europe and America — including the Louvre and the British Museum — rely on Japanese paper to repair ancient manuscripts and paintings.

In these quiet laboratories, East and West literally meet through fibers.

The Science Inside Tradition

Washi’s beauty hides complex physics.

Its long plant fibers intertwine in multiple directions, distributing tension evenly.

That’s why a thin sheet can resist tearing.

Its tiny air pockets let light pass but scatter it gently, creating that distinctive translucence.

Unlike industrial pulp paper, which breaks down over decades, handmade washi can last for centuries.

Papermakers also size the surface with dōsa — a coating of animal glue and alum — to control how ink spreads.

This balance between absorption and resistance gives each sheet its “personality.”

Every step, from beating the fibers to brushing the sheets dry, affects how the paper feels, sounds, and even smells.

Technology today can explain these microstructures in detail, but craftsmen have sensed them for centuries simply through their fingertips.

Their knowledge is scientific — only spoken in the language of experience.

The Modern Journey — Decline and Revival

When Western-style pulp paper arrived in the Meiji era (late 19th century), Japan embraced it eagerly.

Factories could produce tons of paper quickly and cheaply.

Washi, by contrast, required time, water, and skill.

Demand plummeted; many papermakers closed their workshops.

Yet washi never disappeared.

It survived wherever quality mattered more than quantity — in art, official documents, and sacred rituals.

Paper made from mitsumata and gampi, for example, was chosen for Japan’s first banknotes because it resisted tearing and forgery.

After World War II, as Japan modernized, handmade paper seemed destined for museums.

But from the 1970s onward, a quiet revival began.

Designers rediscovered washi’s warmth; architects admired its ability to diffuse light; conservationists valued its strength.

In 2014, UNESCO recognized “Washi: The Craftsmanship of Handmade Japanese Paper” as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity — citing not only its technique but the community spirit that sustains it.

Today, young artisans, including many women and even foreign apprentices, are learning the craft in rural valleys.

Their goal is not simply to preserve the past but to reinterpret it for the future.

Washi in the Contemporary World

Modern washi stretches far beyond scrolls and screens.

In interior design, it appears as lampshades, wallpapers, and acoustic panels that absorb sound while filtering light.

In fashion, it becomes threads woven into breathable fabrics — light as linen, strong as silk.

Luxury brands such as Chanel and Louis Vuitton have used washi installations for exhibitions, drawn by its texture and translucence.

And in laboratories, engineers study nanofiber washi as a base for eco-friendly filters and medical membranes.

The philosophy remains the same: using natural materials with respect, finding strength in delicacy.

Washi’s evolution proves that “tradition” in Japan is not a museum label — it is a verb, a way of continuing.

The Human Element — Touch, Sound, Silence

Ask a papermaker how they know when the paper is ready, and they might say,

“I listen to the water.”

The craft is full of such quiet statements.

Knowledge here is transmitted not through manuals but through rhythm — the motion of the hands, the sound of dripping water, the feel of the fibers as they gather.

Watching a sheet emerge from liquid is strangely moving.

Something shapeless becomes tangible, transparent, alive.

In that moment, one understands why the Japanese word for “handmade” — tezukuri — implies both skill and heart.

The hand itself remembers.

Washi invites the same attentiveness from those who use it.

When you touch it, you slow down.

You notice texture, light, and time.

That slowness is not nostalgic; it is restorative — a small rebellion against the rush of modern life.

Why It Matters — The Philosophy of Enough

At its core, washi reflects a way of living that values balance over excess.

Papermakers harvest only what the plants can regrow.

They reuse water, waste almost nothing, and work with the rhythm of the seasons.

Their craft is sustainable not because it follows new environmental rules, but because it always has.

The philosophy is simple:

Do not take more than you need. Make things that last. Let nature lead the way.

In an age of speed and disposability, this quiet ethic feels radical.

Washi shows that beauty can emerge from restraint, and progress can mean returning to harmony.

Epilogue — A Thousand Years in One Sheet

A single sheet of washi holds more than fiber.

It holds time — the slow boiling of bark, the swirl of clear water, the patience of winter sunlight.

It holds memory — of hands that once dipped, lifted, pressed, and dried, generation after generation.

And it holds hope — that something made carefully, honestly, and in rhythm with nature can endure.

The world may turn digital, yet the need to touch, to feel, to see light through a living material remains.

Washi reminds us that craftsmanship is not a relic of the past but a dialogue between yesterday and tomorrow.

Thin as breath, strong as history —

washi continues to speak, in silence, to anyone willing to listen.

The Japanese version of this article is here.↓↓↓